As recently as the early nineties, it was thought that the human brain did not add any new neurons after around the age of eighteen months. Researchers began to question that idea a few years later, and by 2013, there was evidence that new neurons were growing in the brains of adults, in the hippocampus (an area involved in learning and memory). The idea has remained controversial, however, and a 2018 study in Nature pushed back against that finding.

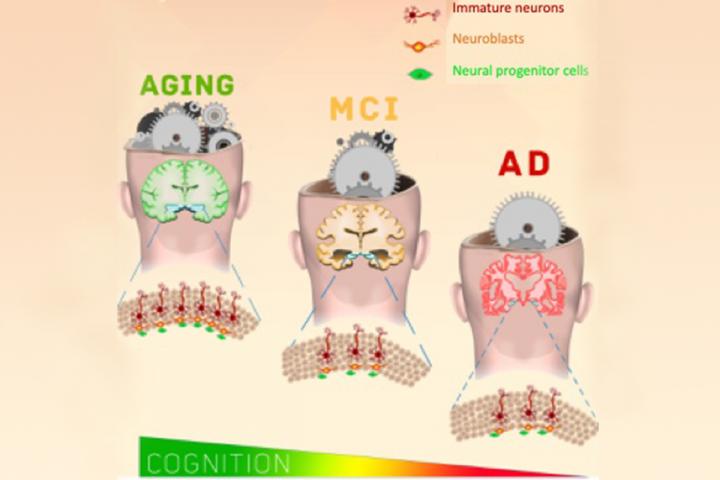

New work by scientists at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC), which analyzed the hippocampus in post-mortem brains of people aged 79 to 99, has shown that neurons do indeed continue to grow in the adult brain, including elderly brains. The researchers found that even when people have a serious cognitive impairment like Alzheimer’s disease, neurogenesis continues, albeit at a significantly reduced rate. This work, which is the first to demonstrate the development of new neurons in the hippocampus of older people, has been reported in Cell Stem Cell.

“We found that there was active neurogenesis in the hippocampus of older adults well into their 90s,” said the lead author of the report Orly Lazarov, a professor of anatomy and cell biology in the UIC College of Medicine. “The interesting thing is that we also saw some new neurons in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive impairment.” More newly developing neurons were present in the hippocampus of people who scored better on tests of cognitive function when compared to the brains of people who scored lower, regardless of brain disorder.

The scientists were able to assess eighteen samples of post-mortem hippocampal tissue from people aged an average of around 90 years. After evaluating the tissue with a special stain for neuronal stem cells and developing neurons, an average of 2,000 neural progenitors and 150,000 developing neurons was revealed in every brain. After looking at subsets of the developing neurons, the team found that in cases of disease or cognitive impairment, there were significantly less proliferating developing neurons.

Lazarov hypothesized that the decline of neurogenesis in the hippocampus is more closely related to cognitive decline, and is not a biomarker of disease pathology. The buildup of plaques, for example, is a pathological feature seen in Alzheimer’s.

“In brains from people with no cognitive decline who scored well on tests of cognitive function, these people tended to have higher levels of new neural development at the time of their death, regardless of their level of pathology,” Lazarov said. “The mix of the effects of pathology and neurogenesis is complex, and we don’t understand exactly how the two interconnect, but there is clearly a lot of variation from individual to individual.”

This research may open up new possibilities in therapeutics for brain disorders. “The fact that we found that neural stem cells and new neurons are present in the hippocampus of older adults means that if we can find a way to enhance neurogenesis, through a small molecule, for example, we may be able to slow or prevent cognitive decline in older adults, especially when it starts, which is when interventions can be most effective,” Lazarov explained.

Lazarov also wants to know if the neurons found by her team in older adult brains are functioning the way they would in younger brains. Learn more about how neurogenesis might be used therapeutically from the video.